In a Dark Matter University-led studio at University of Michigan, students were asked to create two digital collages that embodied their interpretation of how design is deployed as a tool of exclusion or inclusion in the creation of (un)just spaces. This collage by Torri Smith highlights a vision of urban public housing that meets the needs of its inhabitants through generous shared spaces, greenery, and urban farming.

FeatUre

Anti-Racist Frameworks for Transforming Design Education

Antonio Pacheco speaks with Dark Matter University co-founders Curry Hackett, Lisa Henry, Quilian Riano, and Bz Zhang

Image credit: Torri Smith, MArch '21, A. Alfred Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning at University of Michigan; DMU's Foundations of Design Justice course, Spring 2021.

Dark Matter University (DMU) is a distributed network of activist-oriented educators who aim to “work inside and outside of existing systems to challenge, inform, and reshape our present world toward a better future” by reenvisioning design education and practice through collaborative and collective anti-racist frameworks. Forged in the aftermath of George Floyd’s murder and the 2020 racial justice uprisings, DMU has spread to over 15 university campuses across the U.S. and Canada by capitalizing on the wide use of virtual education during the COVID-19 pandemic, instigating new forms of intellectual, artistic, and institutional collaborations along the way. The group has engaged in a variety of theory, representation, and studio courses with the goals of nurturing new forms of knowledge production, building new institutional frameworks, and developing new forms of collective practice, all geared toward reorienting design and design education to address and repair rather than perpetuate racial and social injustices.

Antonio Pacheco spoke with four DMU founders, Curry Hackett, Lisa Henry, Quilian Riano, and Bz Zhang, to better understand the conceptual and pedagogical goals of DMU and to consider how DMU will move forward as in-person education returns in the U.S.

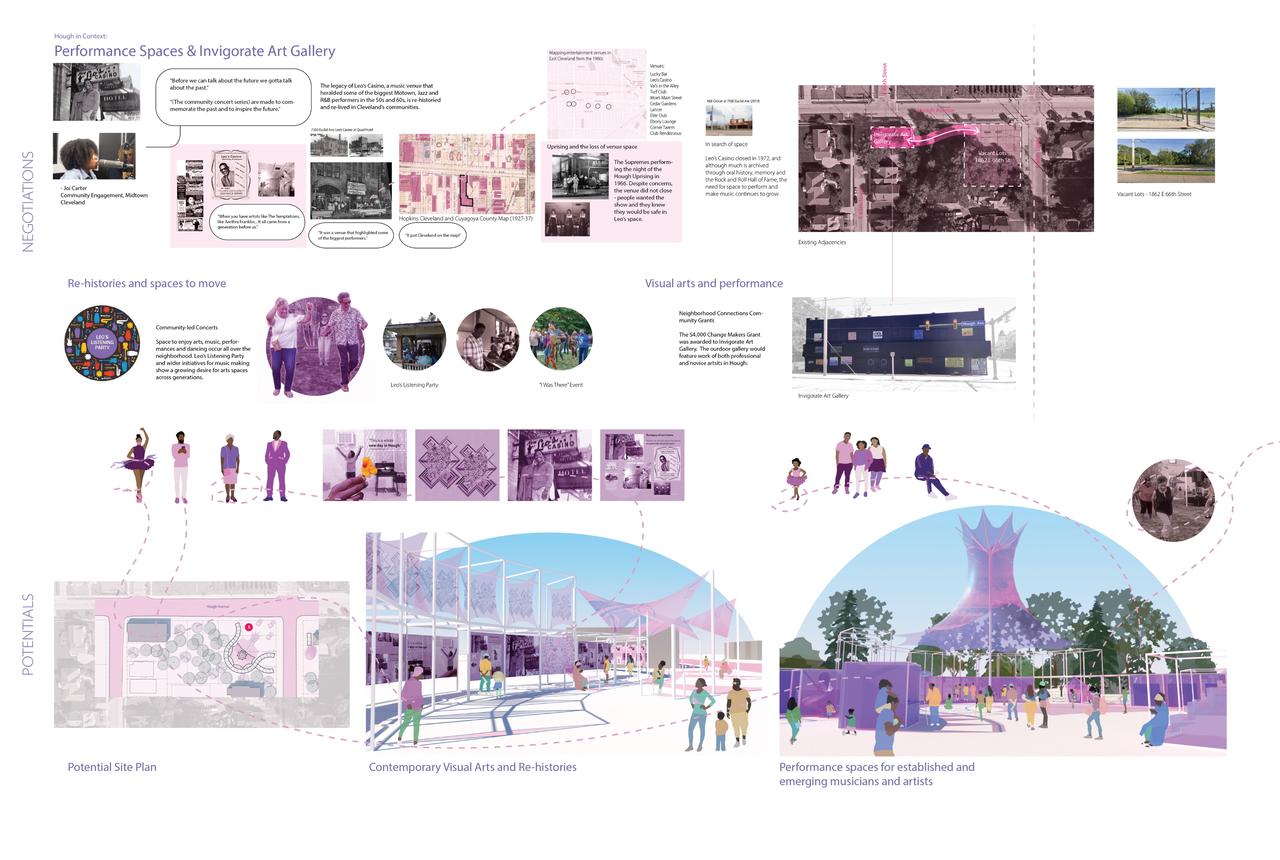

Image credit: Minette Murphy and Thompson Nguyen, MArch Candidates Azrieli School of Architecture & Urbanism, Carleton University; Critics: Jenn Low and Quilian Riano, Dark Matter University; Part of Cooperative Futures studio module.

Presentation boards for a proposal that would convert a vacant lot in Cleveland's Hough neighborhood into a contemporary arts and performance space for established and emerging musicians and artists from the community.

What are some major goals of DMU and how do they intersect with your work?

Bz: A lot of what we’re doing is facilitating—there’s a lot of behind-the-scenes labor that could be considered new models for collaboration. We’re liaising between institutions with very different circumstances and legacies: some are historically extremely well-resourced, and some have been purposefully under-resourced. Facilitating those relationships and those flows of power is something we’re focused on because it allows us to draw on a network of different perspectives. We’ve done a lot of internal work within DMU as well, modeling what collaborative culture can look like within our collective—mentorship, co-authorship, organizing, and so on—as well as in the classes we all teach. Lisa, Quilian, Curry, and so many others are modeling a different kind of studio culture. Something that’s exciting to me is actually lifting the lid and telling our students, “This hasn’t made sense to us, it didn’t make sense to us when we were in school, and it doesn’t make sense to you, clearly, so let’s discuss and find another way together.” And they’ve been so responsive! In the Foundations of Design Justice course Lisa and I worked on, we got to incorporate students’ feedback throughout the semester between four schools—Florida A&M University, University of Utah, University at Buffalo, and University of Michigan—five instructors—Chat Travieso, A.L. Hu, Tonia Sing Chi, Jati Zunaibi, and myself—and all our students. We were sharing notes the whole time, and that became another model of institutional resource distribution, especially with the next Foundations course lined up already this summer at Drexel University, taught by Tya Winn and Venesa Alicea-Chuqui.

Lisa: We want to create new forms of knowledge and knowledge production by bringing that knowledge out of the rarefied world of academia and thinking about how we can learn from all the people we engage with as architects. Design As Protest and DMU have inspired me to refocus everything I do—whether it’s a paper, class, committee, or workshop—to support an activist stance with a focus on design justice, developing equity in the discipline of architecture, and rethinking aspects of practice that allow us to ignore the social impacts of architecture. Everything we do has impact, and if we’re not paying attention to that, we are potentially doing harm.

Quilian: After the murder of George Floyd, groups of us were having conversations about how our educational experiences, both as students and professors, had left us wanting the kinds of things Lisa teaches in her courses. So we began to talk about what changes we might bring to the academic world: how to reimagine the classroom, relationships between faculty members, and relationships between faculty and administration. One of the beautiful things about DMU is that it has been a cooperative effort from the beginning, collective and as broad as possible.

The idea of an architect in the North American context has an unquestioned subjectivity associated with it. Architectural institutions were created for a particular kind of person, usually white men. And while institutions have begun to consider other subjectivities, they’re not questioning that initial premise. We’re interested in what it means to have multiple subjectivities and different collectivities in architectural education, and how institutions might reimagine themselves around that idea. We see that under-examined subjectivity is an issue in the way studios are run, what subject matter is covered, how accomplishment is rewarded, and even what is considered accomplishment. Our Foundations of Design Justice course, for example, is an amazing course. Its syllabus was co-created by Lisa, Bz, and other folks, any two people within DMU can teach it, and usually it’s taught at multiple institutions at the same time. This collectivity disrupts discussions at universities that might not have known how to collaborate like this before DMU came along.

Can you talk about the studio-based components of DMU’s approach?

Quilian: The studio module I co-taught with Jenn Low took place through Carleton University, at the same time I taught a studio with a similar structure/premise at Kent State University, and both were based in Cleveland’s Hough neighborhood, an African-American community. We put together a large network of local stakeholders to question the very act of design with an interest in the specific types of cooperation, collectivity, and negotiation that design requires. We began by studying the history of cooperatives in the African-American community and other communities of color, and focused on the body as a site where politics gets placed. We then amplified these investigations into urban designs that used the neighborhood itself to create spaces of engagement and activism that facilitate processes that could produce the types of spaces the community wanted. All the studio projects included bits of landscape, urbanism, and architecture, and the drawings showed what these spaces could look like when we engaged with the network of people and the systems necessary to make those changes. To me, the studio created a form of situated, contextualized, and systematized architecture that doesn’t just show an image as a final outcome.

Curry: I co-taught a studio called For–With: An Individual Practice Towards Collective Expression, with Jelisa Blumberg at Carleton University in Ottawa, and a seminar with Jerome Haferd called Fugitive Practice: Introduction, Recentering, and Exploration of Black and Indigenous Design Methods. Both courses foregrounded Black performance practices—everything from crip walking to New Orleans second line to voguing—and tried to have students understand these activities as “fugitive practices” rooted in marginalized behaviors that refuse oppressive power by taking space. The studio operated in the same Cleveland site as Quilian and Jenn’s studio, and was, in many ways, an exercise in representation—of bringing Blackness into the architectural canon—and an effort to consider Black spatial practice as a legitimate contribution to architecture. It was a powerful learning experience for all parties involved: we were situating the body in the making of space rather than a building. These explorations were also used to create alternative forms of mapping. For the final review, the students created interactive games that foregrounded collective work to understand who has a right to the public realm, which we all know can be the substrate for aggression against Black and brown folks. We also tried to approach the idea of architecture without knowable outcomes, and without a concern with whiteness.

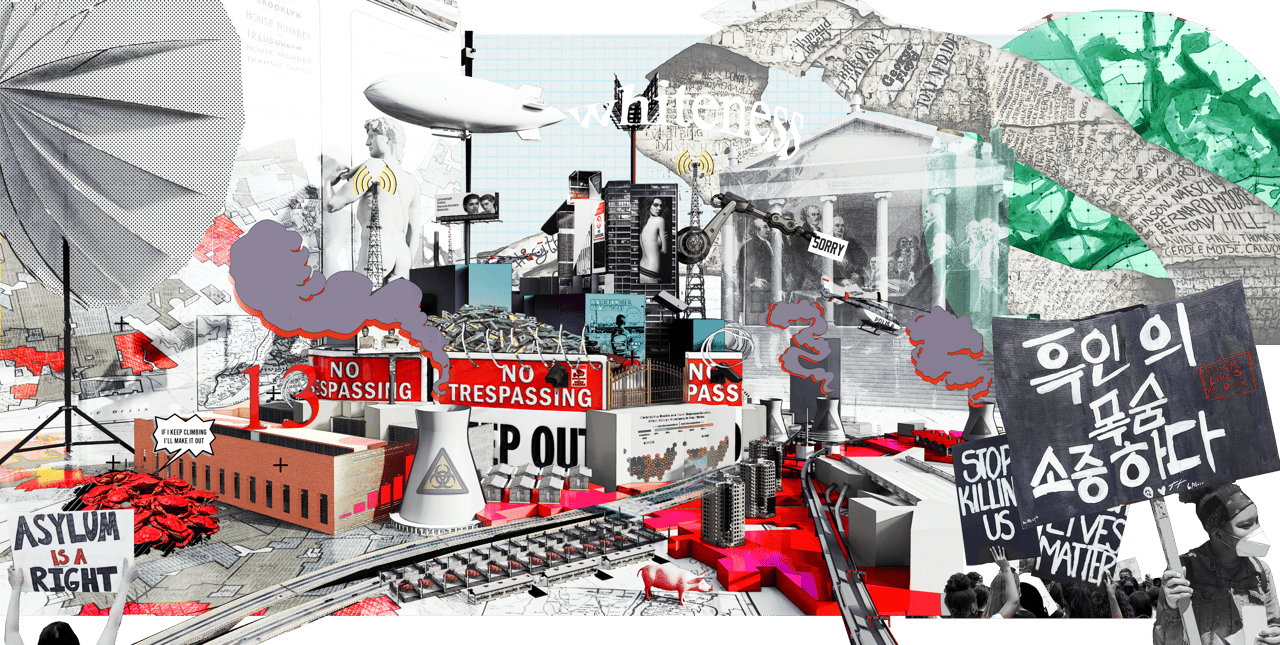

Image credit: Torri Smith, MArch '21, A. Alfred Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning at University of Michigan; DMU's Foundations of Design Justice course, Spring 2021.

A second collage by Torri Smith highlights the ways design is utilized, through redlining, toxic land-use patterns, and overt racism, to harm communities of color.

DMU’s focus on the idea of “process as an outcome,” as a pedagogical model, is quite compelling. How do you envision this way of learning transferring to the “real world”?

Lisa: Architectural education has a responsibility to think past traditional, capitalistic, corporate practice focused on serving a client rather than a community. Our goal is to transform these things dramatically across the board, not just in education. If we want to diversify architecture, we have to attract a much more diverse student body. When I went into architecture, I was inspired by my own experience growing up as a mixed-race girl in the Deep South, but when I went to school, I was taught a straight-down-the-line corporate practice model. I was not given examples of ways I could go back to my community and make a difference. In these courses, we’re talking about how to go back to your community and create transformation, and how to take inspiration from your own experience. The Foundations of Design Justice course exposes students to different ways to practice architecture and make a living, but also to transform community and make real changes in terms of design justice.

Bz: The contemporary manifestation of architectural practice—like all systems of oppression rooted in the Western tradition—is not the only model, and we know that intuitively, culturally, factually, and historically. We know that there are, have been, and will be other modes of design, understandings of space, and lived experiences of the built environment. I think a lot of what we try to do at DMU is create space as educators and activists for those possibilities. So much of professionalized architecture practice is about gatekeeping and, to me, this gatekeeping serves only to make our discipline, skill sets, and professional expertise less and less relevant when, actually, we have quite a bit to offer. The discipline, field, and industry only stand to benefit from making room for these different kinds of intersections.

My understanding is that the DMU pedagogical model is inclusive of students’ perspectives and rights in a way that builds upon existing models. Can you elaborate?

Bz: It’s been really important for us to identify and use our position and platform as instructors to push back against elements of academic and studio culture that we fundamentally disagree with, like using grades in a punitive way or treating students as containers for reified knowledge. Our student-written Community Agreements are really about seeing classrooms as learning environments that are co-created by everyone within them. That’s not to elide power differentials that are real or to flatten the differences between us in that space, but to recognize that we actually all contribute something to that space, which allows for the opportunity to co-create a better classroom.

How will DMU change as education returns to in-person modes?

Lisa: We have talked about what happens if we try to do this in person; does the nature of these courses require online engagement? One of the wonderful things about online engagement is that it facilitates collective knowledge creation: when we are all using a common posting space, whether it’s canvas or Miro board, the students can actually become co-authors of the syllabus. Students used the online tools to transform the syllabus and requirements for the course. I don’t know how you would do that if you were using a physical classroom.

Digital studios have become communal spaces through the virtual format. What’s going to stick around from this experience, and how might that reshape architectural education?

Quilian: I’ve never had the network of people we were able to bring to our module and the final review before. The students said they’ve never experienced something like that. It was a very moving experience, to be honest. I feel like I learned a lot in this studio, and there were real differences in the content, the work that was produced, and the way students responded to it.

Lisa: The jury space is a traditional space where the hierarchies we’re trying to disrupt in traditional education really take place. Some disruptive aspects of those digital spaces are an important part of the process that, even if we did move to in-person teaching, we’d have to think about retaining. As we have tried to transform the entire curriculum at the University of Utah, for example, we’ve learned that no matter what you do in the studio, if you end with an expert review panel and students standing next to their work, you nevertheless foreground precisely the things you’re trying to disrupt in the pedagogy.

Curry: I love everything that Lisa and Quilian are saying. In my studio at Howard, I was fighting to resist the temptation to create a digital facsimile of the in-real-life class format. It was so fun to experiment with using Figma, a collaborative whiteboarding design tool, not just as a proxy for a pinup, but as a way to have students arrive at decisions on the formatting and syllabus of the class collectively. We invited the students to find relevance in other people’s ideas and to arrive at their own collective voice. While I think all of those are certainly feasible and doable in real life, there is something so satisfying about seeing 15 cursors zipping around the screen, or seeing a document manifest in front of your eyes in a matter of minutes.

Lisa: If you want to increase the stature of non-studio classes, like those on gender, race, or queer theory, you have to make the products of that class public in the way the studio review is public. If you can do that, the actual text and the ideas behind design become part of a public conversation, too. And then you can really evaluate whether students have reached their own goals as opposed to whether what they put on the wall matches a kind of disciplined architectural sensibility.

Curry: I started doing what I call the “jumbo jury.” Instead of just having two or three people who happened to be around, I started cold-calling people at all stages in their careers across many professions and disciplines, and just invited them to the reviews. I had 12 students in my studio, and in the last couple of reviews, we’ve had more reviewers than students. I’d have 16, 17, 18 reviewers coming in, and I’d break the critics into groups of three and so. Instead of dragging on into the evening, we’d have groups of five or six people having really intimate conversations simultaneously. There’s a whole new milieu that we can begin to explore when it comes to the format of review, the format of the jury, the format of the work, the format of the studio—all of that is in question. This is super-exciting to me as a relatively young recent graduate and educator.