Feature

IPAL: A More Equitable JOUrney to Licensing

New York schools are seeking support from firms for the Integrated Pathway to Architectural Licensure (IPAL), a more viable option for many students.

by Stephen Zacks

A few years ago, the National Council of Architectural Registration Boards (NCARB) remarked that a gradual increase in equity of gender, race, and ethnicity among early career professionals had been followed by a drop-off in the number of Black designers taking licensing exams and getting licensed. While there was a growing percentage of women, Latino, and Asian architects, Black licensed architects remained static at 2%.

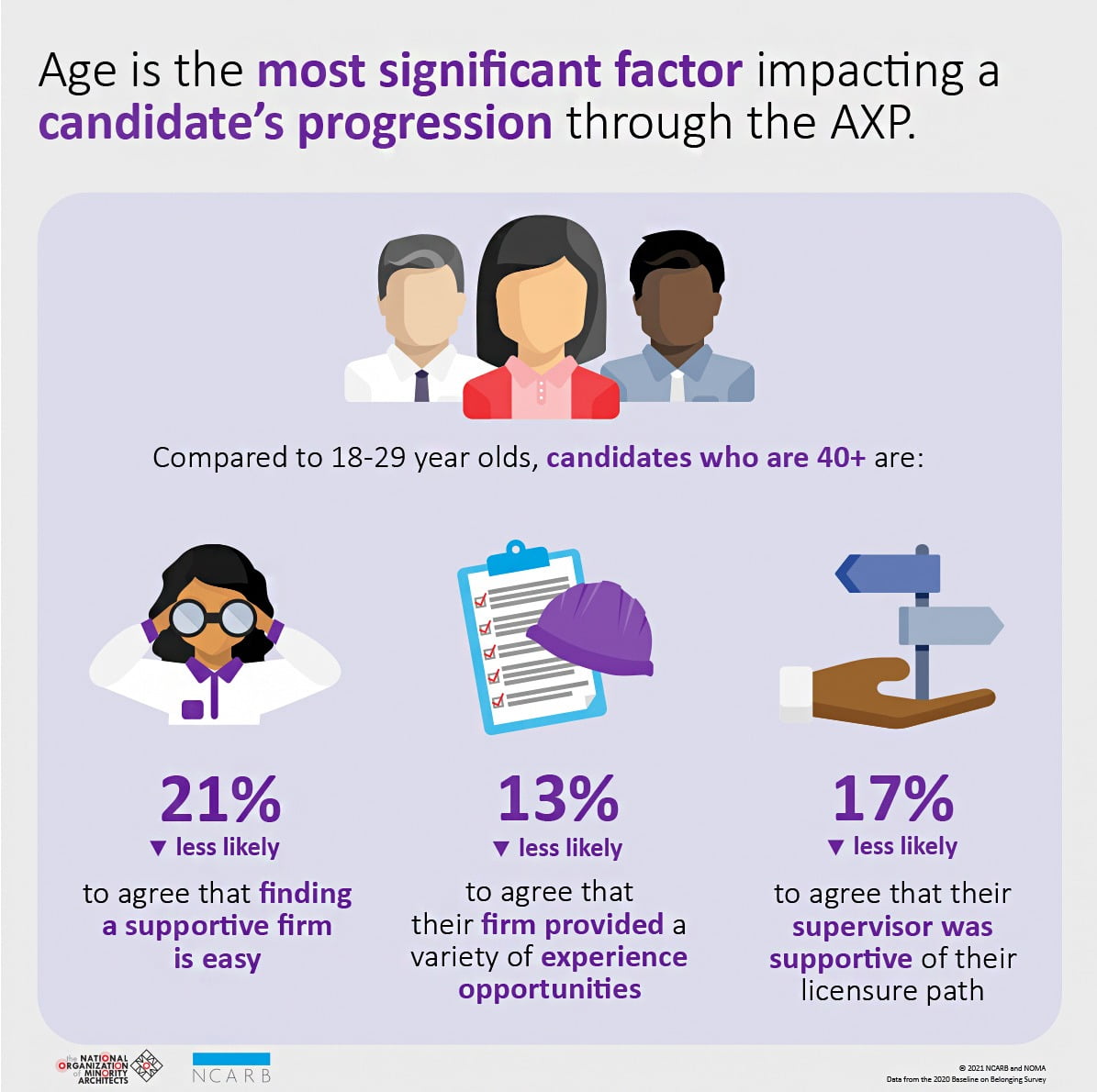

A graphic from the Baseline on Belonging: Experience Report shows that age is the most significant factor when it comes to a candidate’s progression through the AXP, with younger candidates reporting fewer challenges than their older peers.

All images courtesy of NCARB

Working jointly with the National Organization of Minority Architects (NOMA), NCARB last year surveyed 5,300 architectural licensure candidates, recently licensed architects, and professionals no longer working toward licensure to better understand the obstacles to greater equity and representation in architectural licensing. Earlier this year, the two organizations released the first of several forthcoming reports on their findings, Baseline on Belonging: Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion in Architecture Licensing.

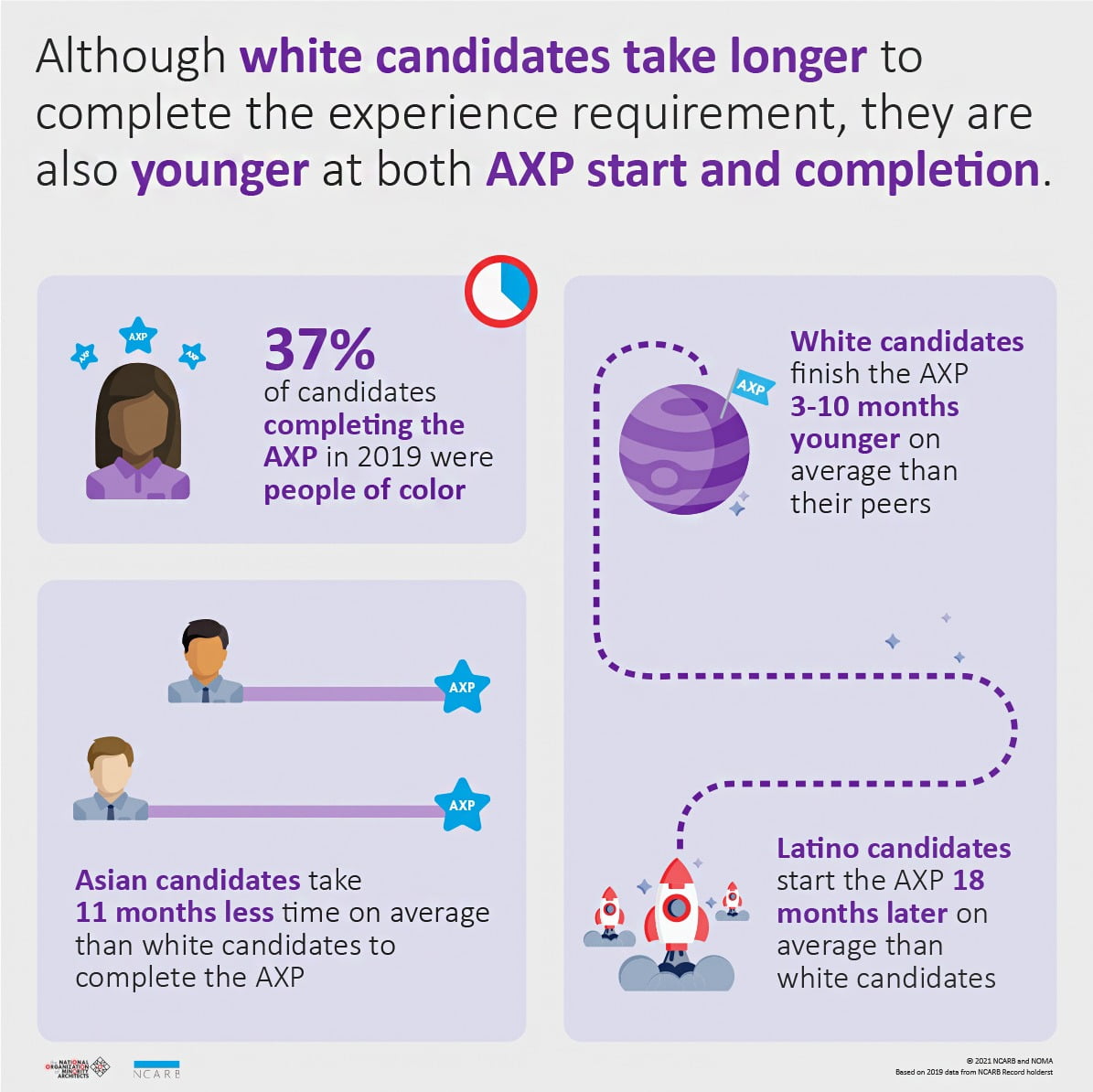

The report showed that while white candidates take the longest amount of time to complete the AXP, they typically start at a younger age and are therefore slightly younger than candidates of other races/ethnicities when they finish.

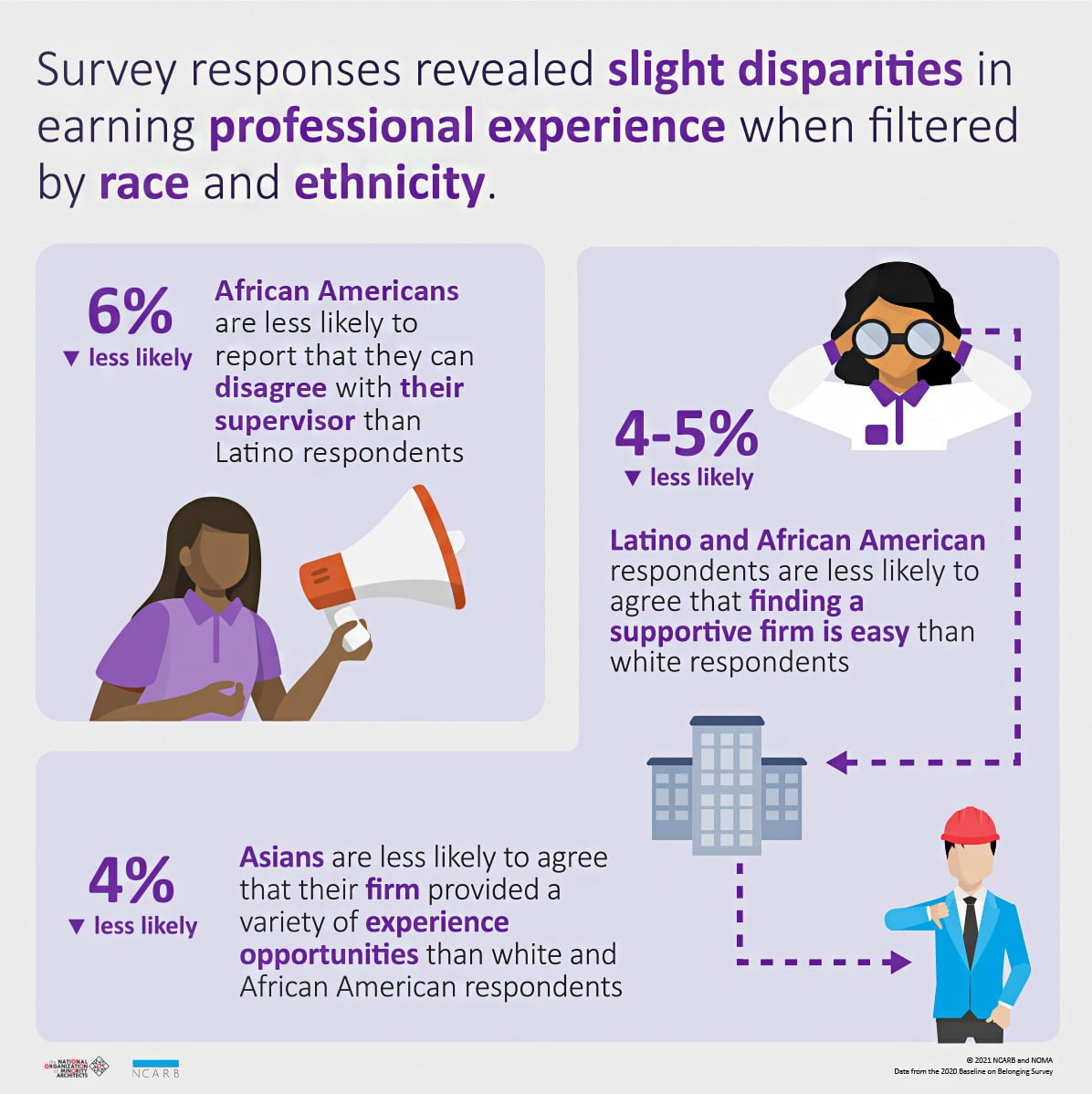

Respondents from Black, Latino, and Asian groups all reported slight disparities in support from their firms in obtaining the experience required to meet licensing requirements, being able to express disagreement with their supervisors, and working the number of hours necessary for the Architecture Experience Program (AXP), one of the three conditions required for licensure, along with education and examinations. Disparities grew when combined with gender, with 6% of Asian and African-American women saying they found it difficult to gain a variety of experiences in their offices.

Systemic disparities are among the reasons why six years ago NCARB pioneered a new pathway to architectural licensure. The Integrated Path to Architectural Licensure (IPAL) allows architecture students to gain work experience and complete their licensing exams while still in school and to graduate with a professional license. Currently, 28 accredited programs at 23 different schools in the U.S. offer IPAL as an option, including 21 M.Arch. programs and seven B.Arch. programs. The first New York State school to be approved was New York Institute for Technology (NYIT), which developed a curriculum and applied to IPAL, but has yet to open the program to students. “We still need to figure out how the hours would work and when the student can start taking the exam during school, but we’re closer to being able to offer it,” says Robert Cody, who was chair of architecture when NYIT applied for the IPAL approval. “We can offer it at NYIT because we have a B.S.A.T. program, which allows for a student to graduate and become licensed in New York. The IPAL program will be in conjunction with our M.Arch program, which would be an additional three years plus some additional work experience required prior to entry into the M.Arch. That’s why it works for us and not for many other schools in New York.”

One underlying reason for the delay and lack of IPAL programs in New York State is the rigorous work requirement of the AXP component of licensure. State law mandates a combined eight years of education and work experience, which go beyond the minimum 3,740 hours in a variety of areas (practice and project management, programming and analysis, project planning and design, project development and documentation, and construction and evaluation) required by NCARB.

For many schools, including NYIT, capacity does not yet exist to combine the experience-based and educational components concurrently within the time frame of a degree. On average, it takes architects 12.7 years from the day they start school to the time they receive a license. NCARB’s IPAL program reduces that to six, but it only really works for students who know as freshmen undergraduates that they intend to practice architecture as a career.

“Scrutinizing licensing standards across all disciplines will help us understand their relevance, return on investment, and value to society.”

—Michael J. Armstrong

Practicing architects support a shorter pathway to licensure. As part of its application for IPAL approval, NYIT sought letters from architecture firms and received widespread positive responses. “We needed support from different architecture firms,” Cody says, “and we received that from small, midsize, and large firms, and also from AIA constituents. We received letters from AIA New York City, Brooklyn, Long Island, Queens, Westchester—so pretty much everybody was on board with this idea. The profession is interested in it, so that also helped New York State make some decisions on changing the restrictions on work experience in conjunction with being in school. We’ve made some headway into being a bit more equitable for advancing students’ opportunities, but we’re still a little uncertain as to how to push it forward in making it all work.”

When filtered by race/ethnicity alone, respondents report only slight differences when navigating the experience component of licensure, especially in regard to their ability to gain experience across the AXP areas and their supervisor’s overall support of their licensure progress.

Another impediment comes from the state legislatures that regulate and the education boards that administer licensure. In some cases, states have encoded mandates for professional licensing that do not permit IPAL as a legal pathway to certification. That has been changing slowly, state by state, with 32 U.S. jurisdictions now accepting the work requirements of the program. Since it began in 2015, 16 students have graduated with IPAL degrees. That number will surely accelerate in the coming years, with hundreds enrolled in the program at various schools. Since most B.Arch. degrees take six years, it’s too soon to know what the consequences will be for increasing equity in the profession. Brittney Cosby, who directs the IPAL program at NCARB, notes that at the University of Florida, where the first three graduates successfully completed the program, all belonged to traditionally underrepresented groups.

Architecture schools have also been slow to adopt IPAL. The issue is not only lack of capacity, but also whether it’s fitting for different types of students. NCARB recently reached out to historically Black colleges and universities to find out why they had not applied to initiate IPAL programs. The reasons they gave were both the lack of faculty resources and the belief that incoming students are not ready. “A lot of their students are coming in with no design experience,” Cosby says. “IPAL is telling them they have to complete AXP and take all divisions of the Architect Registration Examination, when these students are coming in just wanting to know the foundations of the profession. That has been an impediment. The schools are interested in IPAL, but they don’t know if it would be a benefit for their specific program with the level and experience the students bring to the program.”At other schools, especially in M.Arch. programs, the curriculum emphasizes conceptual design rather than professional practice. These programs appeal to ambitious students who want to design buildings that meaningfully engage with architectural history and form, and designers already in the workplace who want to participate in the profession more critically and use their imaginary faculties more extensively. These types of curricula are more oriented toward speculative projects and advanced tools for rendering ideas in 3D drawings, printing, and animations rather than the practice-based focus that IPAL programs would entail.

One of the larger contingents of students enrolled in IPAL comes from Boston Architectural College, which has a 130-year history of employing a practice model of education. It has a practice department within the program, and students simultaneously apprentice to gain work experience while attending school. BAC also has a professor with a special appointment to run the IPAL program, Mark Rukamathu, director of special projects, who serves as its IPAL and architect licensing advisor. IPAL fit naturally into the school’s existing curriculum. “We have a practice program as part of our curriculum, so our students are expected to work while they’re attending our program; it’s part of the degree requirement,” Rukamathu says. “That helped to take care of the hours piece.”

It took Rukumathu 17 years from the start of school until he received his license, making him particularly passionate about helping guide students through the pathway to licensure. BAC not only serves many designers who are still working while returning for an advanced degree toward licensure, it also has an online program that enables students to work during the day and pursue their degrees at night. The school heavily promotes itself as offering a pathway to licensure on its website. “To be licensed the way the law is currently written, you need a certain number of hours,” he says. “It’s 3,740 hours in certain categories, and on average that takes around four years. You’re trying to build that in while in school. That’s the tricky piece of it. It’s definitely trying to add equity and increase the options in the path and time for getting licensed, because traditionally it takes around 12.7 years from the day you start college to the day you get licensed. This helps speed that up.”

In June of 2020, Mónica Ponce de León, dean of the architecture school at Princeton, entered the fray. Responding to an appeal from NOMA Past President Kimberly Dowdell for the architectural community “to condemn racism and take an active role in eliminating the racial biases,” Ponce de León issued a statement calling for the elimination or radical transformation of the licensure system’s examination and practical training requirements. “Both are structured to perpetuate discrimination and inequity,” she wrote. “This exclusionary tactic is inexcusable, indefensible, and must end.”

Though respondents generally feel well-respected and supported by their supervisors, 25% of all respondents indicated that they faced challenges that made it difficult to earn AXP credit.

This was followed in September by an editorial by Michael J. Armstrong, CEO of NCARB, arguing for reduction of B.Arch. degrees from five to four years to cut down on the time and costs of a degree. “When the first step to licensure can only be achieved by spending five to seven years in school, that reality raises questions of access and reduced market competition,” he wrote.

Meanwhile, Armstrong alluded to a movement of policymakers “scrutinizing licensing standards across all disciplines to understand their relevance, return on investment, and value to society.” Led by Libertarian activists at organizations like Institute for Justice, Goldwater Institute, and Americans for Prosperity—funded by the Koch commodities-production-and-trading conglomerate brothers—state lawmakers have been voting on blanket bans on professional and trade licensure with titles like the Right to Earn a Living Act and Consumer Choice Act. In the most extreme cases, advocates argue that the market should sort out winners and losers, and consumers can just sue if they receive poor service or when buildings fail, which could be a recipe for disaster. Under the circumstances, IPAL is a reasonable accommodation that modestly reforms a complex set of problems extending far beyond architecture alone.

Pascale Sablan, FAIA, an associate at Adjaye Associates, became the 315th living African-American female architect in 2014, after struggling for years to pass the licensing exams. It took her 14 tries to pass the seven tests, some of which she passed on the first attempt, others which she took four times.

“That is why I push for advocacy work, community engagement, and considering all clients—not just the ones that pay you, but all the stakeholders who are impacted by your structure and your intervention into the built environment.” —Pascale Sablan

Sablan notes that, at the time, it took six weeks to be notified of the test results, followed by a six-month waiting period to retake the test, prolonging the process. Some of these procedural impediments have been rectified in recent years.

Besides the issues of test-taking and obtaining experience, Sablan argues that better-supported professions are pulling Black women away from architecture, as are the challenges that motherhood places on sustaining one’s career, and the reality that architects (and their property-developer clients) are often rightly seen as enemies of under-represented communities. She urges creating incentives for greater belonging among BIPOC and women through leadership, discussions, infrastructure, support mechanisms, and resources that would allow diverse talent to take on leadership positions and institute policy changes that address systemic issues. “Design is great when it’s designed for you,” Sablan says. “A lot of construction, design, architecture, buildings are rarely designed for and with the local community or reflective of that local community. It becomes a signifier that longtime residents may no longer be able to afford to stay, and new neighbors who perceive cultural rituals as a nuisance, which sometimes escalate into a conflict that the police are called to mitigate.”

It’s not that young people are not exposed to architecture, according to Sablan. It’s that architecture is the problem. “Perceiving the design profession in a negative light is not a misconception but an accurate depiction of the relationship we've cultivated with our profession and those who are socio-economically disadvantaged more often communities of color,” says Sablan. “That is why I push for design justice solutions, advocacy work, community engagement, and considering all clients—not just those who fund the project, but all the stakeholders who are impacted by the structures and design interventions into the built environment. It’s not a matter of introducing architecture to the community through programming. It’s also about creating a healthy relationship between the profession and society, so they can experience the value of the design profession and how we can collaborate to make their lives better, and therefore spark a real interest in getting into the profession.

Editor's Note: At press time, NCARB announced it is sharing licensing exam pass rates by race, ethnicity, gender, and age for the first time. See the news release here.