The Test Beds project by New Affiliates is an initiative to repurpose architectural mockups and provide shade in New York’s community gardens. The project is a collaboration with NYC Parks GreenThumb.

FeatUre

New practices

The 2020 competition asked entrants: How do you choose to shape your practice, define your role and contextualize your work?

By Casey Romaine and Patrick Sisson

New Practices New York, a biennial competition since 2006, serves as the preeminent platform to recognize and promote new and innovative architecture and design firms in NYC. Organized by the AIANY New Practices Committee, this juried portfolio competition honors architects that utilize innovative strategies, both in the projects they undertake and the practices they have established. Meet the 2020 competition winners below.

Image credit: Courtesy of New Affiliates and Sam Stewart Halevy

Brandt : Haferd

Image credit: Courtesy of Brandt : Haferd

From left: Migrate is part of the Harlem Renaissance Pavilion project with WXY, UberEats, Harlem ParktoPark, BodyLawson Associates, and JPDesign; Infinite C's Rooflet is a multi-programmable roof-clubhouse prototype and part of the COVID-19 Memorial project with Curbed Magazine; Beautiful Browns, a single-family residence prototype

The practice of partners K Brandt Knapp and Jerome Haferd wrestles with scale, oscillating between local and regional, public and private, client-driven and multidisciplinary. Before they officially formed their studio, their work revolved around self-initiated projects at the intersection of public art and architecture. Though they’ve since expanded into larger client-driven work, their goal is to continue taking on a range of projects. “We knew we didn’t want to be solely a residential practice,” Knapp says. “We’ve always made sure we’ve had a mix.”

Stemming from their partnership on projects during graduate studies at the Yale School of Architecture, collaboration is at the core of much of their work. For the Renaissance Pavilion, a recent initiative highlighting Black-owned restaurants and businesses on a historic stretch of Adam Clayton Powell Jr. Boulevard in Harlem, the studio designed two parklets, collaborating with other local architects and artists from the area. Knapp and Haferd prioritize building upon connections they’ve developed within the community surrounding their East Harlem office space, aiming to leverage themselves, Knapp says, “as members of an extended creative community.”

In 2019, they won the grand prize at the Zero Threshold Competition, which tasks architects with designing housing concepts for the for low- to middle-income residents of Cleveland’s Old Brooklyn neighborhood, largely populated by seniors in need of more physically accessible environments. Their proposal, “Side by Side,” is a multifamily structure connected by an elevator, with a communal kitchen and shared green space. Part of the competition’s appeal was its intention to facilitate the building of the winning designs, an effort that has been slowed by the pandemic. But Knapp says the experience has shifted the partners towards “realizing some of these ideas about public space, cohabitation, and community engagement in a larger architectural, and even urban, scale.” The remaining challenge is for their small practice to be entrusted with work at those larger scales. “We’ve done a great job at demonstrating our ability to design that work,” says Haferd. The next step is collaborating with larger offices on bigger projects.

“We hope to realize some of these projects in less typical environments for architectural innovation.” —Jerome Haferd

The studio is also in the process of expanding its base of operations. While the pair have lived and worked in Harlem, they now split their time between Harlem and the Hudson Valley, providing an opportunity to partner with local communities within a wider region of the state and beyond.

But how does a studio committed to foregrounding a local practice expand 100 miles north? “We’re figuring out what this regional, logistical practice looks like,” says Haferd. “We hope to shop around and see if there are ways to partner with community organizations, maybe other architects, and realize some of these projects in less typical environments for architectural innovation.” He cites locations such as Cleveland, St. Louis, and Newburgh, NY. Ultimately, their goal is to find balance through multidimensional work that defies a singular label and builds community in the process. Casey Romaine

Bryony Roberts Studio

Images credit: courtesy of Bryony Roberts Studio; photo: WIP Collaborative, Restorative Ground, 2021

Images 1-4: Outside the Lines, a site-specific installation at Atlanta's High Museum, emerged from conversations between Bryony Roberts Studio and self-advocates with disabilities and their allies, with the goal of creating a space that is engaging for all; Restorative Ground is an inclusive landscape in Hudson Square inspired by ongoing research by WIP Collaborative about public spaces for neurodiverse populations of all ages; the collaborative's research has highlighted the importance of providing a range of spatial qualities—high and low stimulation, tactile materials and textures, distinct experiential zones—to create a supportive public environment; Community Platform creates public space by bridging the abandoned train tracks of the Petite Ceinture in Paris

How can an architecture practice create more inclusive public work? For Bryony Roberts, the answer lies in looking outside the field. Truly engaging with the social experience of spaces, Roberts says, “requires a gathering of other kinds of expertise.” Rooted in Roberts’s own interdisciplinary background—which includes education in studio art and architecture and work in historic preservation—her practice unites a range of voices and perspectives through research and design. Her goal is to create spaces that are accessible and interactive, projects she says are “always wrestling with politics of public space.”

Recently, Roberts’s firm thoughtfully considered how designed spaces are experienced across age and physical ability. In “Outside the Lines,” an installation that opened July 10 in the piazza of Atlanta’s High Museum, the studio draws on conversations with self-advocates with disabilities and their allies. Considering not just the physically disabled but those on the developmental and intellectual spectrum, the installation provides a range of sensory and tactile experiences, offering the possibility of engaging a wider public.

The studio has also teamed up with others within the architectural field, joining the recently established WIP Collaborative, a feminist architecture group consisting of seven individuals who work both independently and on shared projects. One such project, an 80-foot-long street activation opening this summer in Hudson Square, draws from the WIP Collaborative’s ongoing research into public space for neurodiverse populations. Roberts says research is integral to her practice. “Every project is a chance to learn more about an aspect of the public realm and to constantly expand what architecture can do,” she explains. Her studio also calls into question what architecture can look like, often incorporating textiles, pattern, and decoration—elements Roberts acknowledges carry a gendered feminine association—and explores ways these elements of craft can be woven into an architectural language that typically excludes them.

“Every project is a chance to learn more about an aspect of the public realm and to constantly expand what architecture can do.” —Bryony Roberts

Addressing what she sees as limitations of dialogue within the field, Roberts hopes to get “outside the myopia” of architecture to create immersive sites reflecting public interest. Her aim is to break conventions, allowing for built environments that are representative of an interdisciplinary technique.

It’s a process Roberts says requires stepping outside of oneself to allow for real collaboration, whether with community groups, users of a space, or other artists and architects. “I spend a lot of time listening and observing,” she notes, “and not assuming I know the answer, or that the answer comes only from architecture.” Casey Romaine

Citygroup

Image credit: Courtesy of Citygroup

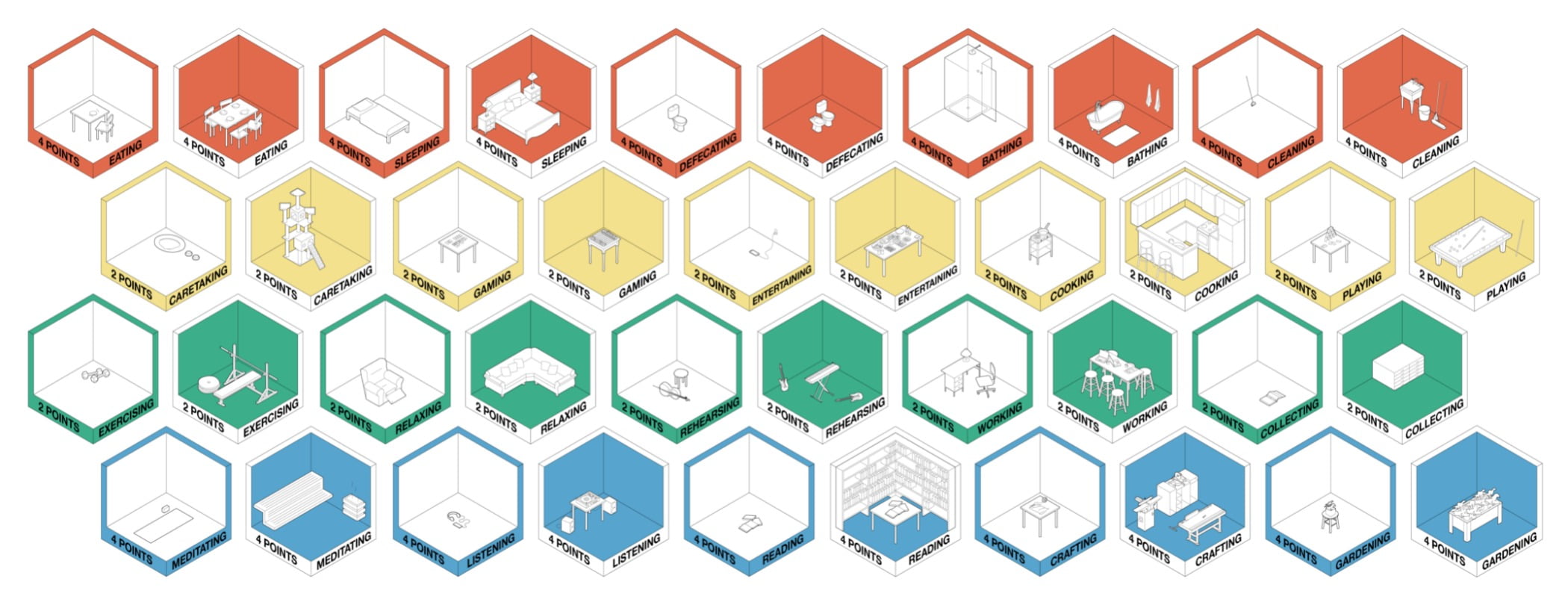

Images 1-2: An in-person demonstration of Alone Together, the Game; the game invites participants to explore new configurations for living space.

Type the name of architecture collective Citygroup into a search bar, and you’ll likely be flooded with results for the banking company, Citigroup. The similar nomenclature is intentional, says Michael Robinson Cohen, who explains that the ubiquity of Citi in New York—Citibike, Citibank, Citifield—speaks to the power of private interests in the public sphere. “For us, the city with a y is a place that should be for the public,” says Robinson Cohen, adding that “the future of the city should be defined by the people who live in it.” Though made up of roughly eight to 10 core members, the collective more broadly considers all participants in the group’s projects as members of a larger Citygroup entity. Fittingly, the collective evolved from a series of debates beginning in 2016 that aimed to foster critical discourse between those inside and outside the field of architecture. “Dialogue is something we want to encourage over monologue,” says Robinson Cohen.

“The future of the city should be defined by the people who live in it.” —Robinson Cohen

Dialogue within the group’s storefront space has since extended to larger conversations with the Chinatown neighborhood surrounding it. Founding member Violette de la Selle says it can be easy to forget that “as architects, you tend to work for the haves and not the have-nots.”

Challenging this, the group has prioritized the concerns of the area surrounding its Forsythe street address.

For their first exhibition in 2018, the collective provided architects and artists with the building plan for nearby luxury tower One Manhattan Square, tasking them with reimagining the plan to challenge constraints of real estate and consider shifts towards affordable housing and communal living. Through the exhibition, the group discovered organizations like the Chinatown Working Group, a coalition advocating for the rezoning of the neighborhood in support of the existing community. Robinson Cohen says the collective is practicing active listening “instead of coming in and saying ‘we have the answer,’” which has led to “finding smaller ways to insert ourselves in their efforts.” To this end, the group has gathered architectural visualizations in support of the Working Group plan, illuminating contrasts between the realities of current developments and alternate proposals, which prioritize affordable housing and sustaining the livability of the neighborhood.

The identity of the collective is still being defined, but there is a focus on creating space for open dialogue and shifts in thinking within the field. “We’re looking for other ways into the discipline,” says de la Selle. Their work has ranged in scale, moving from the urban environment—linking with urban planning groups like the Planners Network—down to the tabletop, through a game designed for the 2019 Oslo Architecture Triennale that explores alternative configurations of living arrangements. Binding the collective is an emphasis on reshaping the habits of the architectural process in search of alternative solutions that might better support the city—with a y—for all its residents. Casey Romaine

GRT

Image credits: Courtesy of GRT

Dutchess County Studio was commissioned by an artist who wanted space to paint and sleep on a 24-acre property two hours north of Manhattan; Guilford House is a low-maintenance, sustainable, barrier-free, and wheelchair-accessible residence for aging-in-place; rendering for a mixed-use adaptive reuse project in the Morris Canal Historical District of Jersey City

One of the joys of historical fiction is experiencing the past not just as prologue, but as dialogue—a different era, aesthetic, and experience in joyful, colorful conversation with contemporary life. The work of Rustam Mehta and Tal Schori, co-founders of GRT, exhibits a similar approach to architectural history, both celebratory and elaborate. It’s found in small, striking features: an entryway reborn with rediscovered plans for terra-cotta peacocks strutting above the door (Fashion Tower in the Garment District), or the soft, rolling edges of a wall enveloping the windows of an 1840s Greek Revival townhouse in Brooklyn, renovated to Passive House standards without losing its 19th-century charm. “We work within the historical context, figuring out what’s important or not, and inserting our own voice when the history doesn’t take precedence,” says Schori.

Mehta and Schori have a shared history, both having grown up in Westchester County, NY, and boasting similar résumés, working for César Pelli and Deborah Berke, respectively. Since founding GRT in 2014, the two have slowly expanded their scale while maintaining an obsession with craft and process. The duo designed their own custom tiles and, while their townhouse renovations often include boldly colored furniture, they’re willing to re-plane and reclaim as much old wood as they can to show off traditional materials and techniques.

Their first ground-up project, Guileford, a stylish approach to a home for aging in place adorned in unstained cedar and painted aluminum, was recently featured in the New York Times. Much like their townhome projects, this design emerged from an obsession with craft and careful consideration; GRT chose materials like Garapa wood because they don’t require any maintenance, and fashioned an interior with custom millwork and bold forms that show off the exquisite wood walls and ceiling. Mehta and Schori are currently working on a mixed-use adaptive reuse project in the Morris Canal Historical District of Jersey City, a podium housing project that brings their approach to a larger scale.

“We work within the historical context, figuring out what’s important or not, and inserting our own voice when the history doesn’t take precedence.” —Tal Schori

“New York City is the most complicated city in the world,” said Schori. “It can make you want to tear your hair out, but you learn about how the city works, how and why buildings look the way they do, and what you can get away with by pushing the boundaries.” Patrick Sisson

New Affiliates

Image credit: Courtesy of New Affiliates and Sam Stewart Halevy

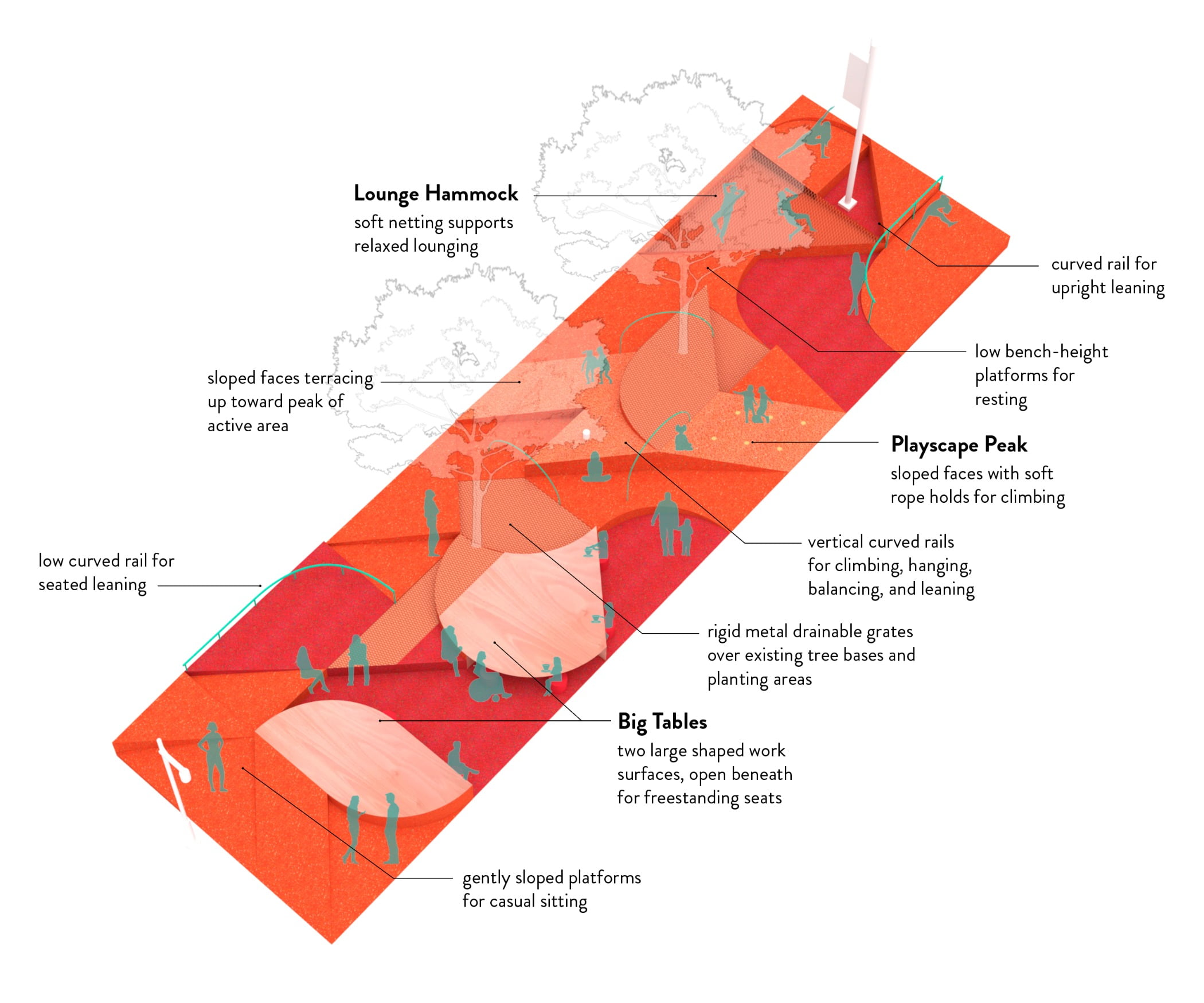

Images 1-4: A rendering of the Test Beds project to use repurposed materials to provide shade in community gardens; the Agnes Denes exhibition at The Shed; Tunbridge Winter Cabin, a painting studio on 65 acres in Vermont's Green Mountains; the East New York Art Studios project transformed a near-derelict tea factory into 7,200 square feet of mixed-use art studios and galleries

There’s reuse, there’s retrofit, and then there’s turning soon-to-be-discarded architectural models into new community centerpieces. The Test Beds project by the firm New Affiliates, a collaboration with the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation, gives new life to the detritus of design. Transforming a discarded mock-up of an exterior section of 30 Warren, a Tribeca condominium, the firm created a shade structure for a community garden in the seaside neighborhood of Rockaway, Queens.

Partners Ivi Diamantopoulou and Jaffer Kolb are self-described opposites who met during graduate studies at Princeton five years ago. They have fashioned a thought-provoking practice out of their debates, conversations, and intellectual curiosity around preservation, adaptive reuse, and creating new architectural relationships. Kolb said Test Beds arose out of considering the “death and life of our own projects.” A series of studio and loft projects—including a former tea factory in East New York turned into an ivory-colored blank canvas for galleries and artist studios—have shown them to be adept at finding new angles for adaptive reuse.

Another example of their deft fusion of real-world challenges and theoretical meditations is an experiment with steel-frame construction in Vermont. Noticing the proliferation of fast-and-cheap steel-frame structures outside of urban areas, a kind of IKEA/DIY design for the masses, the duo decided to experiment with their own prefab steel-frame concepts to see if they could figure out a faster, less expensive design process that goes beyond the big box and still allows a degree of creative freedom and design intent. “Eighty-five percent of architecture isn’t made by architects,” said Diamantopoulou. “We want to reclaim that.”

The firm’s focus on exhibitions—New Affiliates has designed recyclable museum displays that have been part of temporary exhibitions at the Jewish Museum and The Shed—will come full circle, in a sense, when they design an exhibition at Park Avenue Armory later this year. They will also showcase their own work at Sarah Lawrence College in Bronxville, NY, in the fall. As Kolb has said, it’s important to continually interrogate how their architectural practice operates.

"Eighty-five percent of architecture isn't made by architects. We want to reclaim that.” —Ivi Diamantopoulou

“We didn’t start this practice from a space of security,” says Diamantopoulou. “I’m not sure I’d advise anybody to do it; it’s risky. Being extremely reasonable and prudent, that’s how we did it, and thank God it worked out.” Patrick Sisson

NILE

(Now ANY)

Photo credit (above): Tanya and Zhenya Posternak; Image credits (below) courtesy of ANY

Images 1-5: A permanent installation at Café Forgot; the store features a motorized merchandising display that changes with the click of a button; a Hudson Valley Restaurant concept; the dining area is partially buried and food is served at ground level; a creative agency office and apartment.

Editor's Note: Nile Greenberg is now practicing under the firm name ANY (Abel Nile New York) with partner Michael Abel. The work presented above was created by ANY, though the New Practices prize was awarded to NILE in 2020.

Less is a bore. Robert Venturi’s dig at Miesian minimalism became a postmodernist maxim familiar to decades of architecture students and critics, who have seen modernism become shorthand for a streamlined, bland corporate aesthetic. Nile Greenberg, founder of NILE and ANY (a partnership with Michael Abel), wants to remind people of modernism’s “ecstatic” roots.

“In the moment, in the 1920s, the experience of those spaces was an insane daydream, something communitarian and hedonistic, everything you’d want things to be today,” he says.

Greenberg’s work seeks to capture those experimental origins of modernism via process and materials experimentation and exploration. (His new book, The Advanced School of Collective Feeling, explores how interwar ideas of movement and sports shaped what we consider modern design.) His body of work—such as a creative workspace for a graphic designer, and a lightbox-like Lower East Side boutique for brand 6397—exhibits a boldness and sharpness. An accessory dwelling unit he designed for a client in Denver, the Other House, plays with Mies’s Patio House concept for modern materials and the landscape of the Mile High City, specifically shaping the home to fit within Denver’s back alleys.

At a time when so much of our built environment, especially office and retail, is in flux and under reconsideration, the uncertainty Greenberg brings to his work is welcome. His conceptual work highlights an approach that tries to rethink, not just redesign, existing forms. A proposal for all-wood city maintenance structures in New York eschews concrete in favor of a more sustainable material and more open design, a prism on a plinth that offers space for services both cultural and custodial. His Dear Landlord concept, which took first place in the City Above the City Competition, proposed turning the rooftop of the Brooklyn loft building where he lives into a temporary retreat, with a communal vacation home shared by residents that brings upstate upstairs.

“We always think every project needs to be an experiment—the idea that a space has no precedent.” —Nile Greenberg

“We always think every project needs to be an experiment—the idea that a space has no precedent,” he says. “There’s no reason to redo projects. Every time it’s an experiment of some sort, and there are successes and failures, like the scientific method.” Patrick Sisson